Beyond Growth: Systems Thinking And The Catholic Church’s Future After Pope Francis

by Uwe Seebacher on Apr 23, 2025

What the Catholic Church—as a Global Institution and Enterprise—Might Learn from Modern Governance, Succession Planning, and Organizational Culture

Introduction: A Post-Growth Institution at a Crossroads

As we look to the future of the Catholic Church in the wake of Pope Francis’s passing, we find ourselves at a historic inflection point. The world’s largest religious communion – 1.3 billion strong – is not a startup in hyper-growth mode, but a nearly two-millennium institution confronting mature-phase challenges. In 2021 the global Catholic population grew only modestly (up 16.2 million to 1.375 billion, catholicnewsagency.com), with vibrancy in the global South offsetting stagnation or decline in traditionally Christian regions.

Africa alone gained over 8 million Catholics that year while Europe continued a yearslong membership decline (catholicnewsagency.com). Mass attendance rates starkly illustrate this divergence: in Nigeria 94% of Catholics attend weekly, versus under 15% in countries like Germany or France (catholicnewsagency.com). Such contrasts signal that the Church’s future growth will come from new quarters, even as it grapples with secularization elsewhere. In corporate terms, the Catholic Church is a post-growth organization – one no longer buoyed by easy expansion, but needing renewal, efficiency, and deeper engagement with its “market” of believers.

Pope Francis himself often remarked that we are not merely in an era of change, but facing a change of era. The coming leadership transition invites us to apply structural foresight: to ask not just who the next Pope will be, but what kind of leader and system the Church needs for the 21st century’s complexities. As a cross-sectional systems scientist long involved in enterprise transformations, I recognize patterns here reminiscent of other domains. Just as aging corporations must reinvent themselves to avoid the fate of Kodak or Blockbuster, legacy institutions like the Catholic Church must adapt or risk irrelevance. Indeed, business history shows that organizations which fail to anticipate shifts and “act with yesterday’s logic” – to echo Peter Drucker – become reactionary and lose their footing. By contrast, those that embrace strategic agility and predictive insight can thrive even amid turbulence. The Church, dedicated to an eternal mission yet operating in temporal contexts, can likewise benefit from this wisdom.

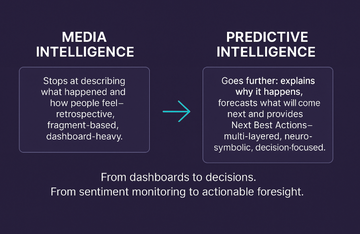

This article will explore how systems thinking and predictive intelligence can illuminate the path forward for Catholicism. We draw parallels to lessons from healthcare (integrating clinical and administrative efforts for patient-centric care) and business (communication reengineering, data-driven strategy) to propose concrete innovations for the Church. Central to our examination is the believer’s perspective – the “Believer’s Journey” from initial faith encounter to lifelong discipleship – and how the Church might manage this journey to enrich the believer experience at every step. Throughout, we challenge some legacy models with candor and humility, invoking principles like “Ecclesia semper reformanda” (the Church must always be reformed) not as mere slogans but as structural imperatives. Finally, we consider the qualities the next Pope should embody, framed in several profiles in readiness, to shepherd a global, culturally diverse flock through a post-growth transformation.

In the sections that follow, we transition from diagnosing the Church’s structural realities to prescribing how it can harness modern methodologies – without compromising its spiritual core – to continue its mission in a rapidly changing world.

Systems Thinking and Structural Foresight in the Church’s Transition

Thinking of the Catholic Church as a complex global system rather than a static institution is key to understanding the current transition. Systems thinking teaches us to see the organization as a web of interdependent parts – theological, cultural, administrative, and human – with feedback loops and emergent behaviors. Under Pope Francis, some shifts toward holistic thinking were evident: for example, the decentralization impulse and the Synod on Synodality (2021–24) sought to listen to local voices, effectively treating the worldwide Church as an interconnected organism gathering feedback from its peripheries. This is akin to a multinational company engaging in global scenario planning: the Vatican initiated a process somewhat analogous to a corporation’s broad stakeholder consultation in crafting strategy.

Structural foresight means anticipating how today’s trends will shape tomorrow’s Church. Demographically, the writing is on the wall. The center of gravity of Catholicism is moving south and east. The College of Cardinals – traditionally Eurocentric – has gradually shifted to reflect this reality, with Pope Francis’s appointments making that body less European than ever (pewresearch.org). (As of 2025, Europe holds 40% of voting cardinals despite only ~21% of global Catholics, while Latin America has 18% of cardinals versus 41% of believers – a legacy imbalance that still needs correction.) Culturally, emerging issues like digital life, climate change, and social justice movements will shape the values and questions of the faithful. A foresight-driven Church would proactively map out scenarios: What does pastoral care look like in an age of AI and remote communities? How will the faith be transmitted in regions where the median age is under 20 (as in parts of Africa), versus regions with aging populations and empty pews (as in much of Europe)? By grappling with such questions now, the Church can avoid simply reacting to crises and instead become anticipatory – turning potential inflection points into opportunities for renewal.

From an organizational design perspective, the Catholic hierarchy can be seen through the lens of a complex adaptive system. Traditional top-down management has its limits in such complexity. In business, it’s well documented that rigid hierarchies and silo thinking undermine adaptation in dynamic environments. The Church, too, can suffer from siloed functions – doctrinal, charitable, educational arms sometimes operating in parallel with little coordination. Moreover, as in any large organization, the Peter Principle lurks: individuals promoted for past service or theological acumen may lack the leadership skills required at higher levels. Studies in corporate settings show that ineffective leaders amplify fragmentation and silos.

By analogy, a bishop or cardinal ill-equipped for modern leadership can inadvertently stifle communication and innovation in his diocese (or department). Acknowledging this truth is not disrespectful; it is an act of intellectual candor needed to design better leadership development within the Church. Just as forward-looking companies invest in training managers to overcome the Peter Principle’s effects, the Church might expand formation programs for bishops on organizational leadership, intercultural communication, and crisis management. Transformational leadership that can bridge traditional doctrine with contemporary human concerns is crucial. After all, leadership quality is often “the ultimate determinant of whether silos will thrive or dissolve” in any complex organization.

Structural foresight also involves reimagining governance. The Catholic Church’s governance has long been centralized in Rome, but adaptive models could delegate more decision-making (where doctrinally appropriate) to regional and local levels, creating a more federated system that can learn from local innovations. This is analogous to how a multinational might grant regional offices autonomy to experiment and then scale up successful practices across the enterprise. Already, we see hints of this: for instance, various countries’ bishops conferences experimenting with new approaches to youth ministry or digital communication. A systems view would encourage the Church to treat such experiments as pilots, measure their results (e.g., did youth engagement rise?), and then propagate effective methods globally – a cycle of organizational learning.

In sum, applying systems thinking, we see the Church not as a monolith but as an ecology of believers, clergy, institutions, and cultures. Each part influences the whole. The leadership transition is a chance to “reset” some systemic conditions – to address choke points (like overly centralized decision flows), reinforce feedback loops (like listening exercises at the grassroots), and set up the structure for resilient growth in mission. With structural foresight, the Vatican can plan not just for the next conclave, but for the next quarter-century of challenges and opportunities.

The Believer’s Journey: From Conversion to Commitment

Amid these high-level structural considerations, the personal dimension of faith remains paramount. Here we introduce the concept of the Believer’s Journey – an analogy to the customer journey in business – to highlight how the Church can more intentionally accompany individuals through stages of faith life. In corporate parlance, the customer (or user) journey maps the end-to-end experience an individual has with a brand or product, from initial awareness through engagement, conversion, retention, and advocacy. Organizations that excel in managing this journey reap rewards in loyalty and satisfaction, outperforming others by wide margins. Likewise, we posit that the Church can benefit from mapping the journey of a believer or seeker as they interact with the faith across time.

What might the believer’s journey look like? It can be envisioned in key stages, for example:

- Awareness and Initial Encounter: The person’s first exposure to the Church’s message or community. This could be through family upbringing, a friend’s invitation, social media, or even encountering Church art or charity. It is analogous to the marketing awareness phase. Here the question is: How effectively is the Church present where people are seeking meaning? Are we “visible” in the digital continent and in daily life conversations? Modern evangelization must ensure that at this first stage, the Church’s image is welcoming and credible.

- Consideration and Inquiry: At this stage, an interested seeker or lapsed Catholic starts exploring more – attending a Mass occasionally, reading about the faith, asking questions. In business, this is the consideration phase, where the “prospect” weighs whether to engage more deeply. The Church’s role here is crucial: do we have accessible, non-judgmental entry points for inquiry? For instance, programs like Alpha or informal discussion groups serve as “product demos” of Catholic life for the curious. A data-informed Church might track participation in such programs and the rate at which inquirers move forward (analogous to conversion rates in sales).

- Conversion and Initiation: The moment of commitment – be it baptism, confirmation, or a personal re-consecration of life. This is akin to the purchase or sign-up moment in a customer journey. It’s a critical threshold: the Church must make this experience profound, authentic, and communal. Liturgical and pastoral quality matter immensely here, as they shape a new believer’s foundational experience.

- Engagement and Growth: After initiation comes the lifelong phase of practicing the faith – attending Mass, receiving sacraments, belonging to parish life, ongoing catechesis. In customer terms, this is retention and upsell: keeping the person engaged and hopefully deepening their commitment (e.g., involvement in ministries, Bible study, or volunteer service). The Church often struggles in this stage – many newly confirmed or married drift away. It is here that a concept of Believer Experience Management can directly apply (explored more in the next section).

- Crisis and Renewal: Real journeys have ups and downs. Challenges like personal crises, doubts, conflicts with Church teachings, or simply apathy can lead to disengagement – the equivalent of a customer considering churn. The Church frequently loses members at these junctures (e.g., young adults leaving after school, or individuals hurt by scandals). Anticipating and responding to these “pain points” is vital. Think of this as customer support and win-back campaigns in corporate terms. Do we notice when someone stops coming to church? Is there a mechanism to reach out, to listen, to address grievances or doubts? A truly responsive believer experience model would treat this stage proactively, with ministries for reconciling and healing.

- Commitment and Advocacy: In an ideal journey, the believer not only remains in the faith but becomes an apostle of sorts – a joyful witness who attracts others. This is analogous to a loyal customer who becomes a brand advocate. The Church has many such individuals (saints being the ultimate examples), and today even laypeople can be powerful evangelizers, both offline and online. Supporting and empowering these advocates (through leadership roles, platforms to share testimony, etc.) closes the loop of the journey, as their witness feeds into others’ awareness and encounter stages.

By articulating the believer’s journey, Church leaders can better pinpoint where our “funnel” is leakiest. For instance, data might show a high fall-off in the young adult demographic after college. That insight should spur targeted strategies – perhaps a revamped young adult ministry or digital content that speaks to their needs. In marketing, customer experience management emphasizes removing friction at each touchpoint; similarly, Believer Experience Management would aim to make each stage of the faith journey as supported and grace-filled as possible. In practical terms, this means designing pastoral initiatives around the user perspective: not merely offering what the Church wants to give, but understanding what the faithful (or seekers) need to receive at each step. It’s a shift from an inward, “we have always done this” mindset to an outward, empathic, and data-informed approach to ministry.

Reengineering Touchpoints: Believer Experience Management in Action

How can the Church tangibly improve the experience of being a Catholic in today’s world? Borrowing from the playbook of corporate Customer Experience (CX) and User Experience (UX) design, the Church can reengineer its key touchpoints with believers. Each interaction a person has with the Church – whether sacramental, educational, or social – is a touchpoint that can reinforce or weaken their faith relationship. A touchpoint could be a baptism preparation class, a Catholic school, a wedding liturgy, a confession encounter, a volunteer service event, a church social media post, or even how parish phones are answered. Leading companies meticulously craft these moments to delight customers; the Church can likewise elevate its attentiveness to believers’ and seekers’ impressions.

Let’s consider a few examples of touchpoint reengineering:

- Digital Presence and Communication: In the digital age, the Church’s website, social media, and apps are often the “front door” for newcomers. Just as companies invest in seamless digital UX, the Church should ensure its online interfaces are inviting, informative, and interactive. Is it easy to find a Mass time or get a question answered on the diocesan website? Is the parish Facebook page active with uplifting content or is it an outdated bulletin board? One could imagine using predictive analytics on search queries to inform content creation – e.g., if many people search “Catholic stance on X issue,” the Church’s platforms should proactively provide clear, pastoral answers. Some parishes now offer chatbots or text lines for quick Q&A, an example of meeting people where they are. By leveraging data on what content engages (clicks, shares, feedback), Church communicators can continuously improve their messaging impact. In business, data-driven targeting has allowed personalization of customer experiences; analogously, a future Church might customize communication (within ethical bounds) – for instance, sending different newsletter content to youth vs. seniors based on their interests, similar to segmentation in marketing. The goal is not marketing for profit, but communication for connection: reimagining the old parish announcement in a form that truly reaches and resonates with each soul.

- Liturgy and Sacramental Preparation: The liturgical life is the core “product experience” of Catholicism. How welcoming and enriching is the Mass experience? While doctrine guides the sacrament’s form, there is latitude in hospitality, music, preaching, and lay involvement. Parishes that have reengineered these touchpoints (for example, introducing greeters, using multilingual readings in diverse communities, incorporating moments of guided prayer for newcomers) often see greater attendance and participation. Feedback mechanisms can be helpful here – some communities quietly survey congregants on their experience or use suggestion boxes (physical or digital) to learn what moves people or what alienates them. Predictive intelligence might even forecast attendance surges (e.g., Christmas crowds) to better prepare staffing and outreach – much as retailers predict peak shopping days. Importantly, any changes should respect the sacredness of liturgy; this is about enhancing accessibility and emotional resonance, not turning worship into a consumer transaction. But even subtle improvements, like clearer signage for newcomers or offering childcare during Mass, can turn an intimidating or frustrating experience into a positive one that encourages return.

- Education and Catechesis: Consider the process of religious education – Sunday school, RCIA (Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults), marriage prep, etc. These are touchpoints where the Church “onboards” people into understanding the faith. A systems-oriented redesign might integrate modern pedagogical insights: adult learning theory, interactive digital content, mentorship pairings, and so on. The Church could, for instance, create an app that complements catechism classes with daily micro-lessons or uses quizzes to reinforce learning, turning what was once a weekly classroom into a continuous, gamified journey. In businesses, e-learning and customer success programs have shown that mixed-media, on-demand content can dramatically improve engagement. A data-informed approach could track completion rates of such programs and adjust them for effectiveness (if many RCIA participants drop out before completion, that’s a red flag to address). Moreover, aligning what is taught (content) with what enquirers actually struggle with (their big questions) is crucial – essentially a customer-driven syllabus. If many young adults wrestle with the relationship between science and faith, are we addressing it head-on? Or if new parents in baptism class mostly worry about how to raise kids with values in a secular world, do we equip them for that journey? Believer Experience Management means we design our educational touchpoints starting from the learner’s context, not just our preset curriculum.

- Community and Social Belonging: One of the most often cited reasons people either stay in or leave a church community is the sense of belonging (or lack thereof). Every interaction that builds fellowship – coffee after Mass, small prayer groups, service teams – is a touchpoint that can be optimized. Some parishes have reengineered this by forming intentional small groups so that no one remains just a face in the crowd. In a large corporation, a similar practice might be onboarding new employees with buddies and teams to ensure they integrate into the corporate culture. The Church could consider a “buddy system” for new parishioners or those returning after a long absence. Data could help here too: a parish might keep a simple database of member involvement (ministries joined, events attended) and if someone who was once active goes quiet, it triggers a gentle outreach – “We missed you at the last Bible study, hope you’re doing okay” – analogous to a company noticing a loyal customer hasn’t made a purchase in a while and sending a friendly nudge. While faith shouldn’t be reduced to numbers, thoughtful use of data can aid shepherds in not letting individuals slip through the cracks unseen.

In all these touchpoint improvements, predictive marketing intelligence has a role. Predictive models, widely used in business, can analyze patterns to anticipate behavior. For the Church, this could mean anticipating needs: for example, demographic data might predict that a certain parish will have a surge of teens in the next five years – giving time to train more youth ministers or develop programs now. Or analysis might reveal that marriages in the church are declining in a region, prompting a proactive effort in marriage preparation outreach before the trend worsens. Just as Amazon or Netflix use predictive analytics to preempt customer churn by personalizing content, the Church could use analytics (carefully anonymized and ethically sourced) to preempt spiritual churn – identifying early signs of disengagement. Imagine a scenario where an Archdiocese notices via its management systems that a significant number of young families stop baptizing children or a drop-off in first communions; instead of reacting years later to empty pews, it convenes listening sessions and targeted ministry in those neighborhoods now. The technology to do this – data integration from parish records, surveys, even social media sentiment – is increasingly accessible. The bigger challenge is cultural: cultivating a mindset that values continuous improvement and responsiveness, guided by data and the Holy Spirit.

It must be stressed that any data-driven approach by the Church has to uphold trust and privacy. The goal is to shepherd souls, not treat people as statistics. Used ethically and transparently, however, data can be a tool for more personalized pastoral care, echoing Jesus’ parable of the lost sheep – knowing when one out of the hundred is drifting and acting swiftly to bring them back. In a world awash with information, those who can predict, adapt, and act proactively hold a clear advantagelinkedin.com. For the Church, the payoff isn’t monetary profit; it’s relevance and relational depth. In essence, Believer Experience Management is about the Church practicing what it has always preached: meeting people where they are, accompanying them step by step, and doing so with the creative intelligence of the era’s best tools.

Cross-Domain Insights: What the Church Can Learn from Healthcare and Business

Interdisciplinary insight is a hallmark of innovative thinking. The Catholic Church’s challenges today, while unique in spiritual context, resemble those faced by large human enterprises across history. By looking at how other sectors navigate change, we can glean ideas for ecclesial renewal. Here, we draw lessons from healthcare, business, and broader organizational development – areas where I have witnessed transformative change – and apply them to the Church.

1. Healthcare – Clinical and Administrative Synergy:

Modern healthcare systems have learned that patient outcomes improve dramatically when clinical excellence (doctors, nurses, caregivers) is paired with operational excellence (administrators, IT systems, process engineers). If the two sides work in silos, errors and inefficiencies abound. Studies indicate that communication failures between clinical and administrative teams are a leading cause of preventable problems in hospitals. In response, leading hospitals instituted multidisciplinary rounds and collaborative decision-making structures so that everyone from chief surgeon to operations manager stays aligned on the patient’s well-being. The Catholic Church has a parallel in the relationship between its pastoral mission and its administrative machinery.

Diocesan offices, finance councils, canon lawyers, etc., might be viewed as the “administration,” whereas parish priests, missionaries, and lay ministers are on the “front-line” of clinical spiritual care. Too often in the Church, these can feel like opposing forces – pastors complain paperwork keeps them from people, faithful complain of bureaucratic hurdles for simple needs, administrators struggle with priests who resist necessary protocols. A lesson from healthcare is that the cure is not to abolish administration, but to integrate it with pastoral work under a shared goal: the spiritual health of the faithful. This could mean involving pastoral personnel in budgeting decisions (to ensure resources match real needs) and conversely training administrators in the core values of ministry (so policies serve people, not vice versa).

Just as hospital CEOs now often include physicians, perhaps diocesan leadership teams could more intentionally blend clerical and lay expertise, breaking the old silo of “ordained vs. lay” in governance. In an era where parishes are being consolidated due to fewer priests, clinical-administrative synergy might also mean empowering lay ecclesial ministers to take on roles once reserved to clergy, analogous to physician assistants stepping in for some tasks of doctors. Ultimately, if all Church personnel see themselves as part of one healing mission (saving souls akin to saving bodies), the coordination and mutual respect improve – and with it, the outcomes of evangelization and service.

2. Business – Communication Reengineering and Sales Intelligence:

The corporate world offers abundant examples of companies that had to reinvent how they communicate and sell to their audience. One striking theme is the shift from siloed communication to omnichannel communication. Customers today expect a seamless message whether they encounter a brand on Twitter, in-store, or via customer service call. Achieving this required companies to tear down internal silos – marketing, sales, customer service, R&D all had to share information and present a unified voice. Those that succeeded saw significant gains; a McKinsey study noted organizations with high cross-functional collaboration outperform others by over 30% in customer satisfaction.

The Catholic Church, in effect, has multiple “channels” of outreach – parish sermons, diocesan statements, Vatican documents, Catholic social media, schools, charities, etc. Do these speak a cohesive voice? Under Pope Francis, efforts were made to simplify and unify messaging (his plainspoken homilies and tweets in multiple languages brought a refreshing singularity of focus to Church teaching on mercy, for example). Yet, at times the Church still issues mixed messages – perhaps a disconnect between what a local bishop emphasizes and what the Vatican emphasizes, or simply an outdated style of communication failing to engage the young.

Communication reengineering for the Church might involve training all levels of leadership in effective modern communication, including listening skills. It might also mean adopting tools for internal knowledge-sharing: imagine a global platform where pastors can exchange successful homily approaches or community event ideas (somewhat like a corporate knowledge base). When one diocese finds a way to bring lapsed Catholics back, that “case study” should be disseminated widely – much as a franchise business shares best practices among all its stores. On the sales intelligence side (an analogy to evangelization strategy), businesses today use data to identify promising leads and tailor their pitch. Similarly, the Church could identify spiritual “lead scores” – for example, areas of high interest in spirituality but low Church presence could be targeted for new missions. If analysis shows that certain demographic groups (say, young urban professionals) are curious about meaning and service but not connecting to parish life, the Church can brainstorm specific outreach (perhaps a speaker series at a pub or a retreat geared to their schedule).

In essence, predictive marketing intelligence in business finds the right customer with the right offer at the right time; for the Church, it’s finding the right person with the Gospel invitation at the moment their heart is searching. None of this means treating faith as a commodity – it means stewarding our evangelical mandate with the savvy of “wise as serpents, innocent as doves.” It also entails measuring results: businesses relentlessly track conversion metrics; the Church might humbly ask, are our current programs actually yielding disciples? If not, we must have the courage to change them, guided by both prayer and evidence.

3. Organizational Transitions – From Silos to Integrated Learning Systems:

Both healthcare and business examples highlight a common thread: breaking silos is essential. In my earlier research on organizational growth, I observed that as entities expand, silos naturally form unless leadership interveneslinkedin.comlinkedin.com. The Catholic Church has “expanded” across cultures and centuries, and silos can take the form of nationalist churches, isolated theological schools, or simply lack of coordination between different charisms (for instance, a diocese and the religious orders operating within it). The Synergistic Leadership model suggests that leaders must intentionally cultivate cross-boundary collaboration to unlock an organization’s exponential valuelinkedin.com.

For the Church, a concrete step could be fostering more collaboration between movements and hierarchy. We have seen tensions in the past – e.g., lay movements like the Jesuit-founded Comunidade de Vida Cristã or the Focolare movement injecting new spiritual energy but sometimes viewed warily by local bishops. In a learning organization model (to use Peter Senge’s term), the Church would treat each of these movements as learning labs from which the whole can benefit, rather than as separate silos. The recent synodal process is a promising move toward an integrated learning system: it gathered insights from parish level, synthesized them at national and continental levels, and fed them into a global discussion. This mirrors how a large company might hold local focus groups, then regional strategy meetings, culminating in a global strategy revision – a far cry from top-down edicts with no input.

The payoffs of breaking silos are significant. Cross-pollination of ideas can lead to innovations (for example, borrowing the Latin American Base Christian Communities model to rejuvenate parishes in Europe). It can also prevent disconnects that cause disillusionment (for example, if the Vatican Curia had stronger representation or consultation from women, might it have foreseen and mitigated some of the backlash about women’s roles?). Research shows that organizations embracing diversity and internal openness solve problems faster and perform betterlinkedin.comlinkedin.com. The Church, as an institution that spans “every nation, tribe, people, and language,” should be the world’s most diverse organization – and could be its most innovative, if it truly harnesses that diversity through synodal, inclusive governance.

Finally, in any organizational transition, there is often the temptation to focus solely on structure and strategy, forgetting culture. But culture – “the way we do things here” – eats strategy for breakfast, as the saying goes. The Church’s culture includes profound positives: a long memory, a commitment to truth over fads, a willingness to sacrifice for higher goals. It also has negatives: sometimes a complacency (“we’ve been here 2000 years, we’ll survive”), clericalism (insularity of the ordained class), and an aversion to risk and feedback (many in the Church bristle at criticism or new ideas, citing tradition). Learning from other domains, any transformation must engage culture head-on. In business turnarounds, leaders often start by modeling new behaviors and rewarding those who embrace change. Pope Francis gave a powerful example by his personal simplicity and openness, setting a new tone at the top. Going forward, church leaders at every level will need to actively encourage experimentation, celebrate “holy failures” that tried to evangelize in new ways even if they didn’t pan out, and instill a culture where speaking up with ideas or concerns is welcomed, not suppressed. In a hospital metaphor, it’s establishing a no-blame culture so that issues are surfaced early (imagine if priests felt safe to admit burnout or doubt without fear – how much sooner could we address those and prevent scandals or dropouts?). In sum, the cross-domain lesson is clear: structure and strategy reforms must be married to culture change, creating an environment where continuous learning is the norm. The Church at its best was exactly that – think of the early Church adapting from Jews to Gentiles, or Vatican II reading the “signs of the times.” That adaptive, learning spirit can and must be rekindled.

Profiles in Readiness: What Type of Successor Does the Church Need?

Profiles in Readiness for Church Leadership – five potential archetypes for the next Pope, each addressing key dimensions of the Church’s post-growth challenges.

Every papal transition brings intense speculation about the next Pope’s background, geography, and ideology. But from a structural and systems perspective, the focus should be on leadership profiles – what blend of skills and vision would best guide a post-growth, global Church at this juncture. We propose five archetypes (not mutually exclusive) as Profiles in Readiness for the kind of leader the Church might require now:

- The Systems Integrator. This leader excels at weaving coherence across theological diversity and cultural plurality, proactively addressing fragmentation in the Church. Just as a CEO might integrate a conglomerate of different business units, the Systems Integrator Pope would bridge gaps between traditionalists and progressives, between the global North and South, ensuring all feel part of one Church family. Key characteristics: a mind for synthesis, a heart for unity in diversity, and the administrative savvy to reform structures that currently work in isolation. This profile resonates with the need to break silos – a Pope who might reorganize the Roman Curia to be more collaborative, or convene think tanks of scientists, artists, and theologians to integrate human knowledge with faith (echoing perhaps Pope John Paul II’s spirit of engagement with culture, updated for now). The Systems Integrator would take seriously the pastoral disconnects – for example, ensuring that doctrine emanating from Rome is communicated in a way local cultures understand, and that local pastoral innovations are reported back to Rome. In an age of polarization, this leadership profile emphasizes cohesion over partisanship, making the Church a home for all her members.

- The Global South Visionary. As the demographic weight of Catholicism shifts southward, a leader deeply attuned to the experiences of the Global South could be transformative. This profile brings proximity to the Church’s growth dynamics and social challenges outside the Western world – be it poverty, persecution, or youthful populations with booming vocations. A Global South Visionary Pope might hail from Africa, Asia, or Latin America (continuing the precedent Francis set as the first Latin American pope) and would inherently prioritize issues like economic justice, interreligious dialogue in non-Christian-majority contexts, and perhaps a less Eurocentric expression of Catholic liturgy and devotions. Key characteristics: cultural humility (able to navigate diverse customs), a missionary zeal reminiscent of the Church’s earlier eras, and an innovative spirit in addressing situations where the Church is growing amidst adversity. This profile aligns with the fact that the fastest Church growth is in Africa and Asia (2.1% and 1.8% annually, versus ~0.3% in Europecatholicnewsagency.com). A leader from these contexts might better understand how to nurture that growth and address its obstacles (for example, the shortage of priests vs. exploding flocks, or how to maintain doctrinal unity when theology is often taught from a European perspective). The Global South Visionary could also rejuvenate the faith in the North by importing some of the vibrancy – think of the way African priests now revitalize parishes in Europe with their fervor. However, this profile must also handle global issues – so it must be coupled with broad exposure and an ability to speak to secularized societies as well, to not alienate the developed world.

- The Post-Growth Navigator. This archetype is adept at leading in post-industrial, secular contexts – essentially the Western world where the Church is not growing but facing contraction and indifference. Just as a corporate turnaround specialist takes the helm of a shrinking company to find a sustainable path forward, a Post-Growth Navigator Pope would focus on re-evangelization of advanced societies, creative use of limited resources, and shrewd management of decline where unavoidable (e.g., responsibly consolidating parishes and repurposing infrastructure while minimizing loss of community). Key characteristics: realism and hope combined – the ability to acknowledge hard truths (like dwindling numbers or reputational damage from scandals) yet inspire renewed missionary fervor; familiarity with secular thought (perhaps a background in science, social analysis or extensive pastoral work in highly secular cities); and openness to new models of ministry (such as empowering lay leaders, digital evangelization, or “small is beautiful” parish communities). This profile is essentially about adaptive leadership in environments where the Church’s social power is weak but the need for Gospel witness is strong. Europe and parts of North America come to mind. Pope Benedict XVI spoke of a “creative minority” of Christians – a Post-Growth Navigator would equip that minority to punch above its weight in moral and cultural influence. He or she (prophetically thinking of leadership style, though the Pope is male by definition) would be comfortable with the Church’s status not as a mass movement but as a leaven in society, and would navigate the Church through further possible shrinkage with strategic acumen – ensuring that even a smaller Church can radiate Christ effectively. Given that Europe is the only continent with a net Catholic decline recentlycatholicnewsagency.com and has an aging clergy, this profile is urgent to consider.

- The Governance Reformer. Even the holiest mission can be thwarted by poor governance. The past few decades revealed areas where the Church’s governance needs reform – financial scandals, lack of accountability leading to abuse crises, opaque decision-making that frustrates the faithful. A Governance Reformer Pope would double down on the institutional reforms Pope Francis began, emphasizing transparency in finances, rigorous handling of misconduct, merit-based appointments, and modern management practices in the Vatican and dioceses. Key characteristics: courage to tackle entrenched interests (Curial politics or local power cliques), knowledge of organizational best practices, and a genuine conviction that good governance serves the Gospel (not viewing it as secular distraction). This profile might entail someone with significant administrative experience – perhaps a Cardinal who cleaned up a diocesan bureaucracy or led a major initiative like World Youth Day successfully. Under this leadership, we’d expect continued audits of Vatican departments, publishing of financial statements, stronger role for lay experts in governance (as demanded by many ordinary Catholics), and pushing decision-making authority down to the appropriate level (subsidiarity) so that the Vatican focuses on unity and doctrine while dioceses handle local matters more freely. Essentially, the Governance Reformer sees the Church a bit like a large NGO or corporation that needs 21st-century governance to avoid dysfunction. The goal is not efficiency for its own sake, but credibility and stewardship: a Church that practices what it preaches in justice and honesty. With trust in institutions at a low ebb globally, such leadership could help restore faith in the Church as an institution, thereby allowing its spiritual message to be heard without cynicism. This profile resonates with calls for accountability: for instance, many Catholics have called for greater lay oversight in abuse cases – a reformer Pope could institutionalize that. Francis made moves here (Vatican finance reforms, etc.), but a lot remains to be done.

- The Synodal Shepherd. The final profile synthesizes a pastoral heart with a collaborative approach to leadership. A Synodal Shepherd is one who leads by walking with the People of God, emphasizing shared discernment, listening, and collective governance (in line with the concept of synodality). Pope Francis championed this model, reviving the Synod of Bishops as a real forum for dialogue and even suggesting the Church itself must become more synodal at every level. A new Pope in this mold would continue that trajectory: perhaps institutionalizing regular synodal assemblies not just globally but regionally, involving laity (men and women) in decision processes in ways never done before, and being a facilitator of consensus more than a monarch. Key characteristics: deep humility, patience for lengthy consultations, and strong communication skills to synthesize and articulate the sense of the faithful. The Synodal Shepherd profile aligns with what we earlier termed experience-based governance – governance that is informed by the lived experiences of believers, not only top-down decrees. This kind of leader might, for example, create advisory councils of ordinary believers around the papacy, or ensure the next Synod includes voting women, or set up a global feedback system for major Church documents (imagine releasing an encyclical draft for feedback – a daring idea, but not impossible in a connected age). While this collaborative approach can be messy – indeed, some fear it leads to confusion – when done well it can massively increase the Church’s agility and credibility. Why? Because decisions will be seen as our decisions, owned by the community, and thus implemented with conviction. It’s analogous to how progressive organizations have moved from command-and-control bosses to agile teams and servant-leaders. The Church would still maintain clear authority in the Pope and bishops, but their style would be more like a chairman of the board gathering collective wisdom and less like an absolute CEO. Arguably, this profile is critical for navigating the pluralism of the modern world: it could help avoid schisms by giving all sides a voice and steering the Church through consensus where possible.

Of course, these five profiles are not mutually exclusive. An ideal leader might embody aspects of all: a globally minded integrator with a heart for the poor, the savvy to reform governance, the creativity to engage secular culture, and the openness to listen. No single human will be perfect, but identifying these needs helps the Church’s electors (the cardinals) and members to discern what the Holy Spirit may be asking for this moment.

Interestingly, in past conclaves, choices often balanced the perceived needs: after a long papacy of John Paul II (a Global South-minded visionary and charismatic communicator), the cardinals chose Benedict XVI, emphasizing doctrinal clarity and a European intellectual approach (perhaps a response to secularism). Then came Francis, whose focus was pastoral outreach, humility, and Global South representation – aligning with the Synodal Shepherd and Global South Visionary archetypes. The next election will similarly be a referendum on what profile is most urgent now. The analysis here suggests that post-growth navigation and systems integration are high priorities, given the Church’s internal complexity and external challenges. A Pope who can consolidate Francis’s synodal reforms, strengthen governance, and still ignite the spiritual imagination of both the poor in the Global South and the skeptical in the West would indeed be a blessing for the Church.

Adaptive Leadership and Experience-Based Governance: Shaping Catholicism’s Next Era

Whichever individual ascends to the papacy, one thing is clear: the mode of leadership needed going forward is fundamentally adaptive. Harvard leadership scholar Ronald Heifetz describes adaptive leadership as mobilizing people to tackle tough challenges and thrive amidst change – it’s about enabling an organization to continuously learn and adjust, rather than just executing routines. The Catholic Church now faces adaptive challenges: secularization, moral credibility, rapid cultural shifts, and technological disruptions. These cannot be met with yesterday’s logic or a business-as-usual stancelinkedin.comlinkedin.com. They require a leader (and leadership team) who actively learns from the Church’s grassroots experiences and is willing to make bold changes in course when the signs of the times demand it.

Experience-based governance is a term that encapsulates this approach. It implies that governance (the processes and decisions of leading the Church) should be grounded in the real experiences of the faithful – their sufferings, hopes, questions, and feedback. In practice, this could mean a number of things: institutionalizing the Synod as a permanent feature of Church decision-making (not just an event every few years, but an ongoing process at diocesan, national, and global levels); creating channels for two-way communication (imagine a global survey of Catholic opinion on key pastoral issues every five years to take the pulse – the recent synod questionnaire was an example reaching hundreds of thousands); and ensuring major decisions (like reforming canon law or issuing a major moral teaching) are informed by expertise from various fields and testimonies from those affected. It is bringing the sensus fidei (sense of the faithful) into dialogue with the Magisterium in a structured way. This is not a capitulation to populism – the Holy Spirit can speak through the least of us, and an experience-based governance trusts in that ancient principle that truth is symphonic, emerging from the whole body of the Church, not just the head.

Adaptive leaders also know the importance of humility. A post-Francis Church will benefit from a continued humble tone. Francis famously asked the people to pray for him at his first appearance and modeled asking for forgiveness on behalf of the Church’s failures. Such humility actually increases authority in the long run, because people trust leaders who admit imperfection and are open to learning. The next era of Catholicism likely needs less triumphalism and more transparency. An adaptive Pope might say, “We don’t have all the answers to these new bioethical dilemmas or social upheavals, but let’s search them together in the light of Christ,” thereby inviting collaborative discernment. Paradoxically, by not clinging to absolute control, the Church’s leadership can gain influence – it becomes a partner with humanity in search of meaning, rather than a lecturer above humanity. This was a key insight of Vatican II’s Gaudium et Spes, which encouraged the Church to read the signs of the times in dialogue with the world.

In concrete terms, adaptive governance might also mean revisiting some inherited structures: for instance, the term of bishops – should it always be until age 75, or could some retire earlier to allow fresh leadership (somewhat akin to term limits)? Could certain issues be decided at regional synods with Vatican ratification rather than everything funneling to Rome? The Church’s canon law already has dispensations for local adaptation; an adaptive governance would use those tools more readily when missionally justified. We might also see more co-governance by lay experts, as mentioned, in areas like finances, safeguarding, communications – bringing in competencies the clergy may lack. All of this requires trust – trust by the hierarchy in lay collaborators, and trust by the faithful that the Church remains guided by the Holy Spirit even as its human administration evolves.

Ultimately, the measure of success for the next era of Church leadership will not be in worldly metrics like growth charts or media approval, but in a renewed authenticity and resonance of the Gospel message. If the Church can speak to the heart of modern humanity – addressing loneliness with community, addressing confusion with truth spoken in love, addressing injustice with courageous solidarity – then it will remain deeply relevant, whether large or small in number. To do so, it must continually attune itself to the lived reality of people (the raw material of experience) and the promptings of the Holy Spirit (often coming through unexpected voices on the margins).

Prof. Dr. Uwe Seebacher’s experience in structural innovation suggests that organizations that endure are those that learn, adapt, and never lose sight of their core purpose. The Catholic Church’s core purpose is unchanging: to proclaim Jesus Christ and build a civilization of love. The ways and means to that end, however, have always changed with history – from house churches, to medieval monasteries, to printing presses, to social media evangelization. The coming decades will likely demand new ways we haven’t even conceived yet. By embracing a stance of openness, rigorous analysis, and creativity – truly becoming a learning church – Catholicism can navigate the post-growth world not with fear, but with a pioneering spirit.

A Vision of Renewal with Academic Candor and Faithful Hope

Standing at this juncture, it’s worth recalling that the Catholic Church has reinvented itself many times before. Moments of crisis often became turning points for revival: the monastic reforms after the dark ages, the Counter-Reformation after the Protestant schism, the global missionary expansion in the 19th century, or the reforms of the Second Vatican Council in the 20th. Each time, what enabled renewal was a willingness to return to the essence of the Gospel and to read the reality of the world with clear eyes. Today’s situation – a world of dazzling technological progress, wrenching inequalities, cultural fragmentation, yet persistent spiritual hunger – calls for that same dual fidelity: to the eternal truth and to the present reality.

Analyzing the Church through the lenses of system science, we have seen that structural and cultural adaptation is not just optional but necessary for the Church’s vitality. This need not threaten the Church’s divine foundation; rather, it honors the Incarnation – the Word taking flesh in each new context. By implementing concepts like the Believer’s Journey and experience management, the Church can show that it cares about each person’s path and is committed to removing obstacles that are of human making. By utilizing predictive intelligence and data ethically, it can steward its resources (human and material) more wisely for mission, staying ahead of trends rather than behind. By learning from healthcare, business, and other fields, it demonstrates humility – truth is God’s, wherever it is found – and refuses to silo itself from the world it seeks to serve. By fostering profiles of leadership that match today’s needs, it increases the chances that the next Pope – and indeed every bishop, pastor, and lay leader – will be equipped to handle their level of complexity rather than be overwhelmed by it (thus sidestepping the Peter Principle trap so common in large organizations.

In writing this analysis, I have aimed to be intellectually candid – not shying away from the Church’s shortcomings in organization and approach – while remaining deeply respectful of its sacred mission. The intent is to offer constructive, evidence-based critique (“speaking the truth in love,” as Scripture counsels). We challenge some legacy models: excessive centralization, communication that only flows one way, promotions based on patronage rather than talent, etc., not to tear down the Church, but to remove barnacles that slow the Barque of Peter. The tone has been strategic because the times demand strategy; but it is also humble, recognizing that ultimately the Church relies on grace. Even the best systems thinking or predictive model is no substitute for the guidance of the Holy Spirit. Rather, these are tools – like the boat and nets that facilitated the disciples’ fishing at Jesus’ direction.

Let us cast our gaze to a hopeful horizon: a Catholic Church that by 2030 or 2040 is more integrated (speaking with unity across continents), more participatory (with laity and clergy co-responsible in governance), more savvy in using knowledge (with real-time insights guiding missionary efforts), and still unmistakably the Church of Christ (faithful to its sacraments, teachings, and preferential love for the poor and marginalized). In that Church, a young believer in Manila or Lagos will feel just as heard and valued as one in Rome or New York. The “believer experience” will be one of encountering a community and leadership that echo the Good Shepherd’s voice – I know mine and mine know me. Such a Church would stand as a beacon of stability and hope in society, not because it clings to old glories, but because it fearlessly lives out aggiornamento – the spirit of updating and cleansing that Pope John XXIII spoke of – in each generation.

In conclusion, analyzing the Catholic Church’s present and future through interdisciplinary foresight reveals immense potential for renewal. The post-growth era can be one of renaissance, not decline, if the Church applies wisdom from all fields in service of its mission. Prof. Dr. Uwe Seebacher’s cross-industry perspective reinforces that whether in business or Church, those who embrace predictive insight and structural innovation while staying true to core values will not only survive turbulence but chart new paths through itlinkedin.com. With adaptive leadership that learns from experience and a humble heart open to God’s guidance, the Catholic Church can indeed enter a new chapter – one where ancient truth and new understanding walk hand in hand. The believer’s journey in the 21st century, then, may lead through unfamiliar terrain, but it remains directed toward the same destination: a living encounter with the Divine, in a community that continually reforms itself to better reflect the Kingdom of God on earth.

Sources: This analysis has integrated insights from contemporary research, including organizational studies on silo dynamics, data on global Catholic trends(catholicnewsagency.com), and lessons from predictive analytics in management science(predictores.ai), to support its recommendations.